by Gail Z. Martin

If you want to get down to bare bones, what defines “urban fantasy” is the setting. By definition, it’s….urban. Often set in a big city, sometimes in a small town, the story also takes place here and now, as opposed to a long time ago and far away. But beyond that, how binding are the tropes? What leeway do authors have to stretch the boundaries of the subgenre? And are tattoos required?

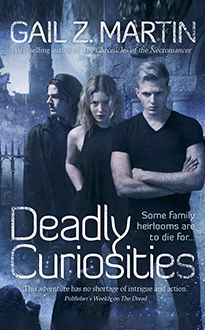

Spend some time in the urban fantasy aisles in a bookstore, or search online, and the tropes will appear. For example, few urban fantasy protagonists in cover art face the reader straight-on. You’re more likely to see an over-the-shoulder look for females (or a body with no head at all) and a heroic profile for males. The women seem to have a penchant for leather pants and “tramp stamp” tattoos and like to hold swords or knives. The men tend to look mysterious, while having something that portends a supernatural element. We laugh at the repetition, but publishers understand the visual shorthand that signals to readers that a book is like others the reader has read and enjoyed. Branding counts, but it’s not iron clad.

With Deadly Curiosities, I requested a well-known cover artist, Chris McGrath, because I admired his work with the Harry Dresden series. Chris does a great job of capturing the urban fantasy feel in both style and composition. I did, however, have some important requests. First, because the book has an ensemble cast, I wanted to see all three of the major characters on the cover. Second, since the novel is set in Charleston, SC and the setting is an essential part of the plot, I wanted to evoke a strong Charleston feel. And third, I wanted Cassidy, my point-of-view character, in street clothes, not leather or lingerie.

Which brings up an important issue. How important is romance in urban fantasy? I’ve read some series, like Sherrilyn Kenyon’s Dark Hunter books, where romance is a primary component. And I’ve read other series, like Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden books and Simon R. Green’s Secret Histories novels, where romance is present but not the driving force of the story. Anita Blake is in a category all her own.

I’ve heard it said that urban fantasy either takes its roots from romance or horror, and maybe that’s true. Romance really isn’t a focus in the first Deadly Curiosities novel. That’s not to say there may not be important relationships that develop as the series goes forward, but as with my epic fantasy novels, the adventure and action are the dominant elements. I do believe that well-rounded characters have relationships of all different kinds–friends, family, neighbors and lovers. Weaving those secondary characters into a series grounds it in a sense of reality and gives the reader insight into the main characters through the quality of his or her interactions.

I was on a panel at a convention with Laura Anne Gilman and Rachael Caine where we were hashing out what the “urban” element brought to urban fantasy. It was a fascinating discussion, because at the heart of it lay our fears and beliefs about cities and places where large numbers of people live in very close proximity. A lot of urban fantasy requiures the anonymity of a large city and its wide diversity in order for the plot to function. (The Sookie Stackhouse books, with their small town setting, is an interesting exception.) That facelessness makes it possible for strangers to pass unnoticed, and for our heroes to move around without attracting too much attention. And it taps into our fears about people we don’t know, and the psychological distance we create even in crowded conditions.

Cities make great fantasy settings for a variety of reasons. They have a lot of history, and the opportunity for plotlines that comes from having a very large number of people passing through them. Cities also have infrastructure, new and forgotten. Big public buildings, subway tunnels, maintenance passages, sealed-over cellars and storm drains–all present scary but intriguing places to explore, areas our subconscious just knows are teeming with things that want to eat us.

Big cities also have big crimes, and the population density means that every city has a lot of dead people. There’s also a transience to cities that makes them appealing settings, since so many people pass through them preoccupied with their own hopes and fears. We’re very aware of the darker side of cities: the muggings, the disappearances, the runaways and vagrants. Most of us know what it’s like to walk down a dark street glancing over our shoulders, or be the last car in a shadowed parking lot. It’s not hard to imagine dangerous creatures waiting for prey down every narrow alley.

It’s easier to hide secrets in big cities. I grew up in a small town, and if I ever did anything wrong, six people had called my parents to tell them about it before I ever made it home. (That kind of thing does wonders to keep you on the straight and narrow.) For better or worse, everyone eventually knew everyone else’s business. The good side of that resulted in neighborly help and plenty of casserole dinners when someone got sick or injured, or had a baby. The bad side was an undertow of gossip and the pressure to conform. But in a big city, there’s anonymity. It’s so much easier to be a faceless part of the crowd, to pass unnoticed, to die alone. Stories are born from that.